What I know about creativity comes from spending over 20 years in different creative fields. And since one of those fields is research, I’ve also always had the time (and the duty) to reflect on this human endeavour. Where did it start? Maybe when I won tickets to a circus at a school-wide drawing competition when I was just in second grade. Maybe in long talks with my grandmother who had written and published two books while raising six children as a single mum. Maybe when I was a media artist exhibiting in museums all around the world (ok, mostly in Europe). This sounds like bragging – narrator voice: it is – but I mention it to establish credibility. Additionally to having grown up the way I did, I also taught classes about making art and entertainment with digital technology since my PhD years. And I’ve done some design research into aspects of the creative process in game design. Even my PhD is partially rooted in Design Thinking (and partially critical of some of its manifestations). So, I can say I know a thing or two about creativity. Just enough to know that I know nothing.

In this newsletter I will write about creativity in fine art as an example. Most creativity today happens in commercial settings, in an economic context that I mostly leave out. I would never say that fine art is beyond economic necessities1 – it’s just not what I am concerned with in this tiny polemic about Generative AI. So let us leave the elephant in the room, in plain sight, a majestic grazing beast that has already consumed all and does not always have to steal the show.

What is creativity?

My personal view is that creativity is a process with a result, but the result is not necessarily tangible. A simple example of a creative process is painting an image. The artist starts with a blank canvas, applies paint, and at some point stops and has arrived at a painting. Yet is even this case so simple? The artist brings their life experience to the process, so the painting has started long before the first brush stroke is applied. The artist might paint over the same painting several times, only the last one being “published”. Are there also economic reasons or purely artistic reasons to regard a painting as finished? If the painting goes to a gallery, what paintings are shown beside it affect how the painting is seen by visitors. Paintings are actually sculptures – a hill I will die on – because they are three-dimensional. They change with the distance you view them at, with the viewing angle, with the light that falls on them. If the painting creates a scandal, which doesn’t happen that often but nevertheless has happened in the past, it is seen differently again. The personality of the artist also sticks to the painting, tainting it. To summarise, even in this most classical case of a creative act it is impossible to tell when it starts and when it finishes and what exactly the product is.

How can we take this bundle of causes and effects and separate them a little bit so we can get a clearer picture (pun intended)? First of all there are considerations leading up to the core part of the creative act, to the moment when the main product, in the above case the painting, is created. Most importantly, the result space is usually constrained before the act of painting starts. The canvas has specific dimensions that dictate how large the painting will be. The choice of paint limits the creative possibilities further (e.g. oil paint dries fast, necessitating specific techniques of layering). A time frame might also be decided for in advance. A lot of constraints come with affordances2: water colours lend themselves to outdoor scenes and paintings that require a certain viewing distance to “come together”. In a way, affordances are just a different way of looking at constraints.

Every painting starts within a context of its creation. There is no blank canvas. The painter always has prior experiences they bring to the table. They might try to bring a certain feeling across to the viewer. They might just have an image in their mind they want to get out. They might be paid to paint a specific scene or portrait. They might just admire a person, situation or place. They might draw from their memories or a photo they saw in the newspaper. They might draw purely from their intuition. There are hundreds of starting points but one thing is certain: the painting process has already started before the first brush stroke3.

Before the actual product is created, preparatory design takes place. In visual arts, this is usually called sketching, in video games pre-production, in special effects pre-visualisation. Quick throw-away designs are created, often a lot of them, and then a curation process leads to one or more sketches that serve as references for the later work. Often, this process is iterative and goes into more and more detail over time. In painting, the painter often transfers a part of this sketch to the canvas, to serve as a template.

Then the actual painting process starts. It is, like most truly creative processes, an iterative process of multiple stages that bounce between creation and evaluation. The painting itself informs the next step. There can be a master plan in place but even if the painter is very strategic in their approach, they will be guided in the execution of the plan by unforeseeable observations. If the painter is less strategic, they will be even more guided by what they are doing while they are doing it. In general, creative processes go through phases of addition and subtraction. Form4 is accumulated and then form is removed. Over and over again. Depending on the medium there might be more or less planning. More planning usually means that more time has to be spent in the sketching phase, and more creative decisions are taken before the actual paining process. At some point, the painting is “done”. This is a decision and not triggered by the painting having achieved any specific state. Unlike a bridge that, at some point, serves its purpose, cultural products are only finished when the artist makes the call. Of course, external influences might trigger this call. If there is a limited time budget available, or if the exhibition date is coming up, painters might speed up the process. Some paintings can keep requiring more work and never reach a state where the artist would decide it’s the right moment to stop. Work ends at some point though5 unless it’s the Sagrada Familia we’re talking about.

As a next step, the painter usually frames the painting (or has it framed). The frame changes the painting and also contextualises it. It becomes part of a class of paintings that have this type of frame at that point. Or a part of the class of paintings that have no frame. This, too, is an artistic decision.

Finally there is the long process of curation, a process that never stops. Not only does the painter select which painting goes where – or economic pressure will decide it for them – but galleries also present paintings adjacent to other works of art. If the work doesn’t go to a gallery it will still end hanging beside something. Never displaying the painting is also an act of curation. Over time, a painting will end up in many different contexts. One could say the curation process only stops with the destruction of the art piece but even then the painting might live on in other media. An echo that never stops, just gets weaker over time.

There are whole books written about creativity but let’s work with these seven concepts for now and look how Generative AI connects to all of them, how this new paradigm of creation manifests in these stages of creativity.

Generative AI in the creative process

In order to contrast painting, I will focus on image generation when talking in this chapter. While the same can be applied to other modalities, it just fits better to how I started.

An AI artist will also first set up some constraints and lean into some affordances. The choice of technology is one of those. If they use Midjourney, they are aware of the creative range of that framework as well as the available parameters. They will also be aware of the aesthetics that the Midjourney model excels at versus those where it delivers poorly. If they have experience, they will work with those constraints as a guiding affordance. Models with open datasets allow the artist to learn about the reference space of the technology they are using, guiding them in the technological choice. Additionally, many artist add seemingly arbitrary constraints to the way they work, further narrowing down the expressive range.

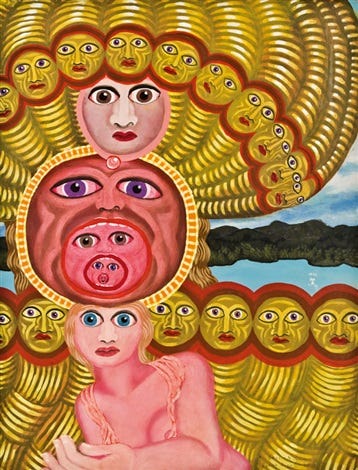

Most successful AI artists have experience in other art forms. Those are part of the context they are working in. They might even be more interested in the conceptual implications of AI technology than in its aesthetic abilities. A lot of them work very actively with the implications of using technology that was trained on our cultural heritage, juxtaposing the old with the new, the established with surprise.

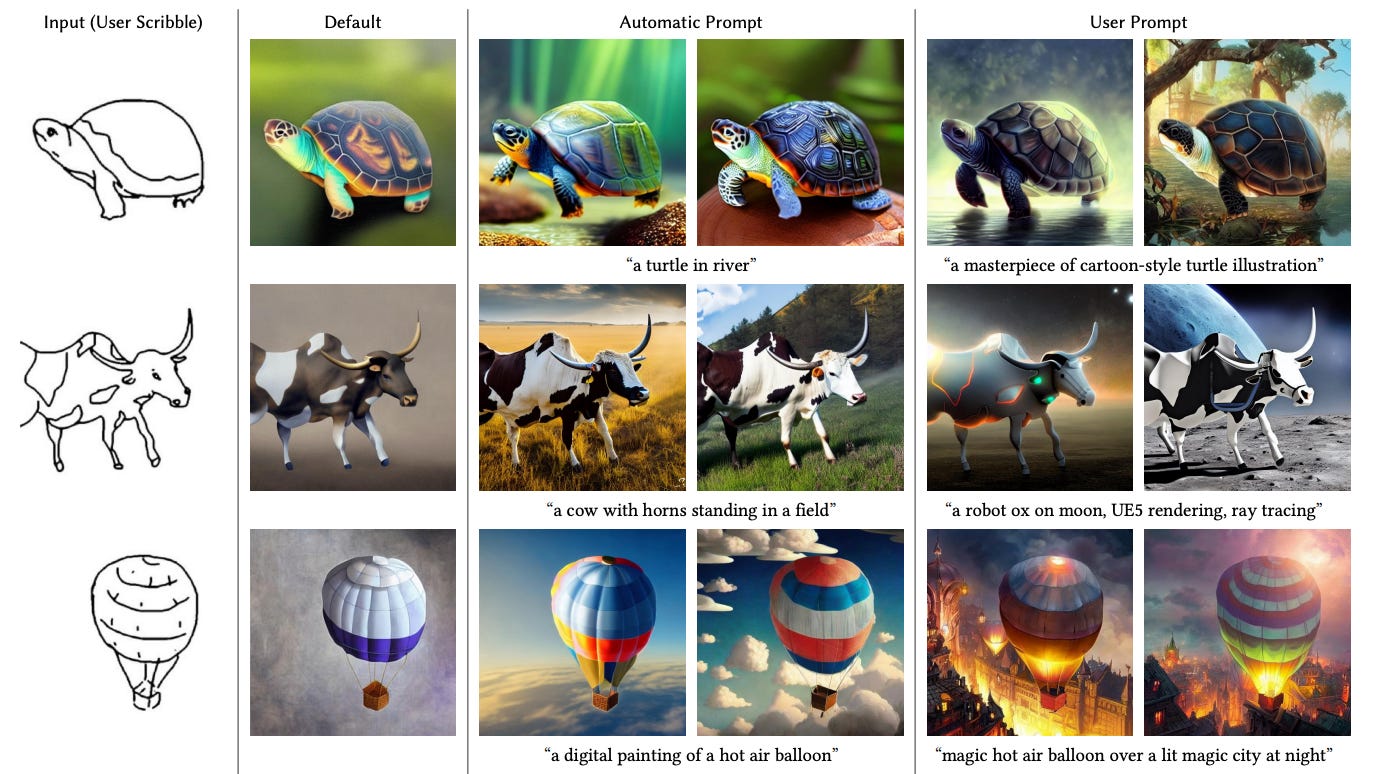

Recent months have seen a wealth of new methods being introduced that help with the sketching process in AI-generated image creation. ControlNet6 allows to work with a base image that dictates the overall shape of the result. PoseNet7 detects the pose of a person in a video or image and can then be used to replace that person by using it as input in ControlNet. Algorithms that provide more control over the image generation process are necessary in order to predict more of the outcome. Of course, prompts are also just constraints for the model and similarly reduce the range of potential result images. Prompt engineering is a way of sketching if the artist has enough experience.

Midjourney displays all generated images in the Discord server you are using it and offers a handful of options to iterate on them. This iteration happens in public, which means that there is a collective learning process. Apart from making variations of an image, the artist usually makes slight adaptations to their prompt until they reach a point where they decide to stop. Just like with a physical painting, this process is guided by more or less of a plan depending on the artist and the situation. Some artists jam with the system, hoping it takes them to interesting places. Others come with a more specific idea of the outcome and try to home in on it.

As the next step, AI artists take the image (or several images) out of the context it was created in and into the context they want to present it in or continue working with it. They might overpaint it in traditional digital tools, out-paint using more AI tools, or print it and work with it in the physical space. They might turn the image into a part of a collage or of a comic page. This is quite similar to the above-mentioned framing process in that it transfers all the associations of the target medium to the image. Once the image has become part of a comic it will be read as a comic panel. The framing has huge implications for what we see when we look at the image.

Finally, as well as at many points leading up to this, curation happens. No artists publishes all of their works. Most creations never get a lot of eyeballs. Platforms highlight some works of art and others just vanish in the ever increasing amount of visual content online. Some art works have a different purpose altogether and serve as inspiration for other, not AI-generated works. Concept art that is only used for a single discussion would be an example of this kind of art. Concept art that was only necessary to think through a visual concept is another one. Art that only exists to inform a traditional art process exist too.

Nothing is new. Everything is new.

To me it seems like we desperately need a more nuanced view of what changes Generative AI brings to the creative process. These systems do not simply regurgitate existing cultural artefacts. Neither do they always replace the creative process with an automatic one. It is also very clear that artists with an existing artistic practice can create more interesting works of art using AI than others. The technologies are so new that it is very hard to gauge what, if any, foundational shifts will have happened when the novelty wears off. We’re still in the middle of the hype cycle, maybe even close to the start, than the end.

What can be said with certainty is that the tools that are available right now support different aspects of the creative process. Midjourney excels at iteration but has a very limited expressive range. This limitation makes images generated with this model recognisable, which is not necessarily to be viewed negatively. Acrylic paint also comes with a specific aesthetics that is recognisable and not suitable for all kinds of images. Maybe new aesthetics are the most interesting area to explore with machine learning.

Personally, I’m more interested in supporting than in replacing parts of the creative process8. This is not what all artists are interested in and that’s fine. I want to make software that allows you to play with the medium you are working with. I want to make software that lets you explore and surprises you. I want to make software that lets you interact with our cultural heritage in new ways. I want to make software that is a little bit dangerous because I believe art needs to have an edge or it turns out blunt. I want to make software that lets humans feel creative. I want to make software that is a tool for thinking more than a tool for production. I want to invent bicycles – not sports cars, not mass transit solutions, not tanks – for the mind.

Ironically realising that was one of the reasons why I stopped being a media artist. The economic reality of fine art is ruthless and pervasive. Successful fine artists are often just entrepreneurs who cater an audience they know well. Nothing wrong with that but I didn’t want to be an entrepreneur in that area.

We’re using Norman’s and not Gibson’s view on affordances here: "...the term affordance refers to the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used. [...] Affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things. Plates are for pushing. Knobs are for turning. Slots are for inserting things into. Balls are for throwing or bouncing. When affordances are taken advantage of, the user knows what to do just by looking: no picture, label, or instruction needed." (Norman 1988, p.9)

For my uncle, a painter, it was super important to make his own canvases before starting to paint. I think he came up with the painting while doing that boring repetitive task. And of course he also just wanted to save money.

I’m using the term “form” instead of “material” because in sculpting, form is accumulated by removing material.

I’m ignoring renovation of paintings and also how the decay of a painting can be a part of the creative process.

A technique for guiding a diffusion model.

E.g. I am not sold on writing software that replaces the act of writing entirely with curation. I think curation is only one part of what we do to reach an aesthetic goal. And I think replacing too much of the writing task will inevitably result in shovelware.