The bubble of the internet around me has been having a field day embracing or rejecting Ted Chiang’s article titled Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art. After reading it over the weekend I felt inspired to formulate my thoughts and write this reply. I think the article is well intended – it keeps talking about how important intention is, after all – and so is my reaction.

Why is this topic dear to me? Not because I’m working with AI, but because I’ve been a practicing artist for many years. I’ve had about two dozen exhibitions in various countries on this planet, the most exciting one definitely Manifesta 71. I don’t want to kick off the are-games-art discussion. So I will just say that every medium can produce artworks and things that only few people would consider works of art. I’m personally a very picky person when it comes to artistic works and my dislike for ontologies always shines through. That means in my opinion – that you don’t have to share – there is no strict boundary where something turns from mundane object to an artwork. It’s more of a gradient. And with time, something might become an artwork. Later it can easily drift out of the sphere where it is regarded as such. The quality “artwork” is not immanent to the work but externally assigned, for a while, by someone, for example me. So what is my working definition of art? It has to touch me emotionally or intellectually or both – I don’t care if it touches you, unless you reveal its qualities to me. It has to have value for me beyond its monetary value – I don’t care if it has the same value for you. These are the only criteria for me. I know that this view is very subjective. And yet, surprisingly many artworks that have been curated by museums check those boxes2. And a lot of “lesser” works do, too.

One thing that a lot of art that I love has in common is that it is made with awareness of the medium. A movie that knows it’s a movie. A video game that exposes the seams of the medium. A book that plays with what a story is. Again, this is not a criterium to be fulfilled for something to be art – it is one more way to touch me, by teaching me something about how the (mediated) world around me works. I admit that this is a matter of personal taste and not everyone gets as excited when they hear a scratching on the fourth wall as I do.

Now where does the artistic quality, the craft3, fit in? If a text is badly crafted, maybe lacking precision, that hampers its effect on the reader. That lack does not have to be an intrinsic quality of the text. Some texts age very well – or can be revived with a fresh translation – and others lose their relevance over time. Gladly, not all texts are written for eternity, and why should they? Being culturally relevant for a short while is fine. The same holds true for music, video games, statues, poetry, and all other art forms4.

I could write a long critique of the Calvinist5 concepts of relating effort with spiritual power that Chiang’s piece is based on. I could argue that writing a piece about why A.I. can’t produce art and then describing an artwork produced with AI in the text makes the title seem a tad sensationalist. I could write about my experience, that in order to produce any art work a lot of ephemeral products have to be created, and ask if AI is allowed to help with those. I could complain about the fact that it is naive to think the AI makes the artwork when it is clearly a human artist in collaboration with a compressed representation of human cultural history who facilitates the act of artistic creation. I could criticise that the simplistic view of prompting presented in the article is obviously a straw man. I could bring up cases where great artists have stolen in the past and the artwork was still relevant, though the artist should not be glorified anymore. I could argue that Sturgeon’s law makes no exceptions and no one can expect it to.

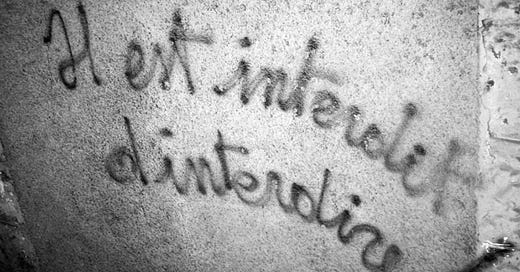

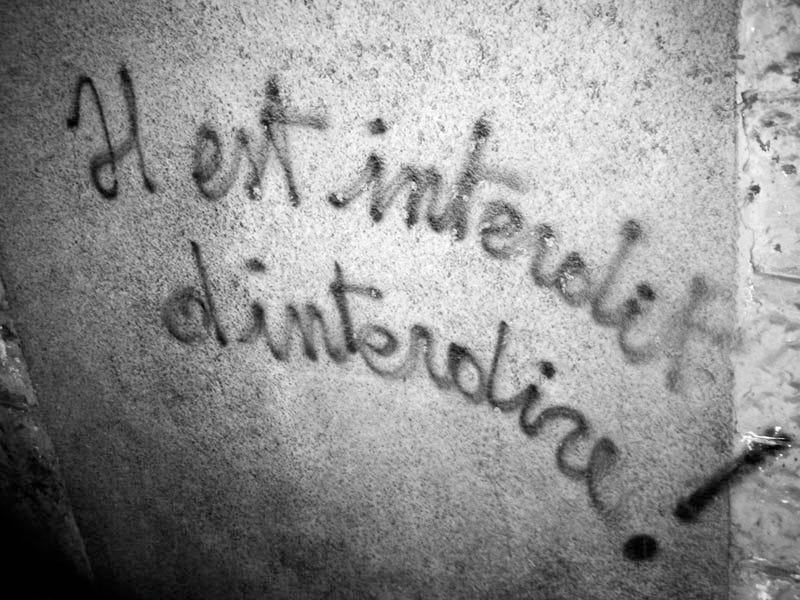

But beyond this paragraph I don’t want to concern myself with a text that forbids artists to work in a specific way. The same text has been written by the same people when electric guitars, mobile phone cameras, video games, books, and any other new medium came along. There will always be a gatekeeper. I will instead focus on pushing back against one single line of argumentation in the article: the need for decision making to make art. The need for control. I think this, too, is a far too simplistic and entitled understanding of art. And I can’t have that particular gate kept. I want both, art born out of control and art out of control.

Marina Abramovic held her groundbreaking performance piece Rhythm 0 in Naples in 1974. She put 72 objects – from roses to a loaded gun – on a table and stood still after giving the audience the following instructions:

Instructions: There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired.

Performance: I am the object. During this period I take full responsibility.

Duration: 6 hours (8 pm – 2 am).

There were a handful of decisions to be taken for creating this art piece: selecting the objects, the venue, and the time, for example. There was also the monumental decision to hold still for 6 hours in order to allow the audience to learn something about themselves. But the performance became art only by the artist relinquishing control. The audience themselves were the puzzle piece to complete the artwork.

For centuries (and most likely longer), artists have developed techniques to deliberately reduce the amount of control they have over the process of creating art. Automatic writing, cut-up technique, improvisation in jazz, situationist interventions, blues, pottery, punk, procedural content generation, and the musical dice game are all examples of this. Are the artworks created using these techniques superior to others? Of course not. But we would deprive humanity of a method for jolting us out of our routine if we reduce art to a careful sequence of decision making. We would lose creative freedom if those techniques are not allowed to be used as inspiration leading to the creation of (more controlled) art pieces, as intellectual toys, and as fringe artistic practice.

The process of creating a masterpiece is rarely a straight line. Only in hindsight can the decisions be regarded as having been clear. In reality, creating something new is usually a messy process of iteration, guessing, gut feeling, experience, trial, and error. It is a decision making process full of decisions that get taken back. Artists use all kinds of crutches to get from the empty page (that was never empty because no one starts from nothing) to the moment the artist (or the deadline) decides it’s finished. And then the process continues once the audience engages with the work, curators frame the piece in relation to other works, critics write about it, and an opinion is formed on social media networks. It only stops once the artwork is forgotten – which further underlines how little of its artistic quality was immanent in the first place.6

Generative artificial intelligence can be seen as yet another tool helping to voluntarily let control slip for a little while during a convoluted creative process. For getting feedback before exposing a work to the real audience. For getting inspiration when the well is dry. For creating unreliable and unpredictable dynamic elements in an interactive experience. The most average representation of an object in human history can serve as a reference, or as a topic for critical reflection7. Will A.I. ever produce art? I have no clue – we have to make it sentient first and I’m in the camp that thinks that we’re not really on the fast track to get there (and that’s fine). Will semi-automatic processes together with artists and with audiences produce art? Sure. They have done so in the past and will not stop at any gate, no matter how well it is kept.8

I decided to quit art because I wanted to make video games. I did that for roughly 10 years before returning to academia. Since I used the same methods for making art, doing research, designing video games, and making software, I don’t separate between those practices as much as most people.

The presentation of those works in context, thanks to curators and art historians, and perfect lighting, thanks to architects and technicians, helps.

Please, as always, when you see something in my writing that could be sarcastic, treat it as such. It is meant as slightly aggravating stimulation. I am perfectly aware that craft and artistic quality are not synonymous.

It does of course not hold true as an absolute truth. It holds true for me and that’s all that matters, because if something touches me, chances are high it touches others too and has some immanent qualities in that moment, in a specific context. I’m a bit eccentric but not that different to a standard human. But please feel free to just like other things than me. I care enough to ask you why something matters to you and am always eager to get inspired.

I grew up in a Catholic country and live in a Scandinavian protestant place now. Scandinavian means it’s more influenced by the Dutch and German reformists than by the Swiss. The reform here was fuelled by revolutionaries more than hardliners. But also it was very openly about money and independence from Rome.

Or, maybe, that particular tree makes a sound when it falls unobserved in the forest. It does not matter. Until someone digs up the work and sees new relevance in it.

I agree that “AI slop” is a result of Generative AI but nowadays I encounter it far more in my spam mails and LinkedIn messages than in artistic works. Sure, for a while people posted bad generated images on social media, but that has mostly stopped in my feeds and the few who still post such images are running interesting experiments.

This all being said, I think there are many ethical issues that urgently need to be addressed when it comes to Generative AI. And there is also the issue that vanilla outputs from most models are frustratingly boring – mostly because no models are made for artistic purposes. That has very little to do with art though…